Makabe Jin and Ogawa Shinsuke

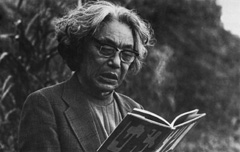

Rural poet Makabe Jin met Ogawa Shinsuke through the production of the documentary film Magino Story—Pass. A monument with the poem “Pass” inscribed on it was built in the Oshimizu forest in the middle of the Zao Mountains, and a grand unveiling ceremony was held. The film was commissioned for the occasion out of a desire to document local peasant poet Makabe Jin and his philosophy. Up until that point, even after Ogawa Productions had relocated to Magino Village, they had not met face to face. The title Pass is taken from this representative work of Makabe’s, and here he recites his own poetry and expresses his determination about the way he has lived and where he’s headed. This is truly Makabe’s history of the Showa period. Irokawa Daikichi described Makabe’s recitation of his own poetry by saying, “what we see is not an intellectual with a sense of shame, but an indigenous peasant poet who is almost audaciously grounded.” This film began with Ogawa Shinsuke’s affection for Makabe Jin. Not only the film Pass, but all of Ogawa’s works use humanity both as a point of departure and one of arrival. It goes without saying that his love and affection for the people of Magino Village never changed. One recalls the day near the end of Makabe’s life when he reached his arms up to Ogawa and said, “Mr. Ogawa, please keep up the good work,” and Makabe held Ogawa’s hand for a long time. And how they made the floor of the hospital wet with their tears.

—Kimura Michio

Ogawa Shinsuke

Ogawa Shinsuke

Born in Tokyo in 1936, Ogawa served as assistant director at Iwanami Productions from 1960, and participated in the Ao no Kai film study group with Higashi Yoichi, Iwasa Hisaya, Kuroki Kazuo, and Tsuchimoto Noriaki. Ogawa went independent in 1964 and made his first films Sea of Youth (1966) and A Report from Haneda (1967). His films were supported at workplaces and universities throughout Japan in the midst of the Zenkyoto student movement. He founded Ogawa Productions in 1968 and went to live in the farming village of Sanrizuka while producing the Sanrizuka series, which depicted the movement in opposition to the construction of Narita International Airport. Continuing to make films from the viewpoint of farmers, in 1974 Ogawa moved to Magino in Yamagata Prefecture’s Kaminoyama City, where he filmed A Japanese Village—Furuyashikimura (1982) and Magino Village—A Tale (1986) while growing rice and observing life in farming villages. His dedicated work as an organizing member of the first YIDFF in 1989 was instrumental to the festival’s success. He passed away on February 7, 1992. |

YIDFF Opening Screening

Magino Story—Pass

(“Magino monogatari: Toge”) JAPAN / 1977 / Japanese / B&W / 16mm / 43 min

JAPAN / 1977 / Japanese / B&W / 16mm / 43 min

Director: Ogawa Shinsuke

Photography: Okumura Yuji

Sound: Uriu Toshihiko

Mixing: Kubota Yukio

Appearance: Makabe Jin

Producers: Iizuka Toshio, Fuseya Hiroo

Production Company: Ogawa Productions

Source: Athénée Français Cultural Center

“The pass is a place that forces decisions, that flows with the clear melancholy of parting.” So goes a short poem by Makabe Jin published in the poetry journal Shijoritsu in 1947. Makabe was a Yamagata poet who played an important role in Ogawa’s move to that prefecture; he was the person who caused Ogawa to discover the “face of the true peasant farmer.” A memorial stone inscribed with this poem had been dedicated to Makabe on the occasion of his 70th birthday. Ogawa filmed Magino Story—Pass using that poem as a motif. It referred to Ogawa’s own “clear melancholy of parting” from Sanrizuka. On the other hand, for Makabe the “pass” signified the bridging of a gap between the experience of war and the new direction of the postwar era. Makabe wanted to illuminate the history of the farming village via myths treating Mt. Zao as a god of agriculture, and through the old people’s stories of the struggles over the distribution of water among their rice fields that were common not so long ago. It is an expression of Makabe’s strong desire as both peasant farmer and poet to “write a personal history that becomes a history of Japanese agriculture.” In capturing the peasant-poet’s pride through his detailed depiction of Makabe, dressed in a straw cloak and hat against the rain, Ogawa crossed a “pass” all his own.

“The pass is a place that forces decisions, that flows with the clear melancholy of parting.” So goes a short poem by Makabe Jin published in the poetry journal Shijoritsu in 1947. Makabe was a Yamagata poet who played an important role in Ogawa’s move to that prefecture; he was the person who caused Ogawa to discover the “face of the true peasant farmer.” A memorial stone inscribed with this poem had been dedicated to Makabe on the occasion of his 70th birthday. Ogawa filmed Magino Story—Pass using that poem as a motif. It referred to Ogawa’s own “clear melancholy of parting” from Sanrizuka. On the other hand, for Makabe the “pass” signified the bridging of a gap between the experience of war and the new direction of the postwar era. Makabe wanted to illuminate the history of the farming village via myths treating Mt. Zao as a god of agriculture, and through the old people’s stories of the struggles over the distribution of water among their rice fields that were common not so long ago. It is an expression of Makabe’s strong desire as both peasant farmer and poet to “write a personal history that becomes a history of Japanese agriculture.” In capturing the peasant-poet’s pride through his detailed depiction of Makabe, dressed in a straw cloak and hat against the rain, Ogawa crossed a “pass” all his own.