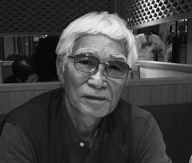

Juror

Adachi Masao

[Juror’s Statement]

[Juror’s Statement]

I’ve heard many stories of directors who come from abroad, who say “Yamagata” with a sense of intimacy. They leave their countries full of enthusiasm, thinking, “This is the capital of our creative spirit!” and return with cheeks flushed with excitement from having participated in this festival.

But now, what first comes to mind are my memories from when Ogawa Shinsuke had just received the New Director’s Award from the Directors’ Guild of Japan, and the many quiet conversations we had then.

The idea was first that films should be made by hand. Or rather, that they should not just be made, but they should also bring spectator and maker close in deep conversation. We wanted to create a space like that, as quickly as possible.

Later, I proposed that cinema should be a struggle and a movement, that films could only speak, could only be made if they confronted their times. I told Ogawa that as soon as possible he should start gazing upon the history of agricultural fundamentalism and the current state of agricultural production, that he should start making films with that gaze. Ogawa nodded thoughtfully.

In the end, the space that we spoke of became none other than Yamagata. I later saw in Ogawa’s films that he had dedicated himself to the rice plant.

In another conversation that I exchanged with Sato Makoto, who made Agano River, we spoke about how we must create films that smash the common notion that drama and documentary are separate things. Sato died amidst that creative struggle.

This is the first time I participate in this “Yamagata.”

I do not go solely to immerse myself in deep emotion, or my memories of my friends. Rather, while embracing these memories of filmmakers who passed away amidst bitter struggles in their creative worlds, I go to meet the resolve of people engaged in new struggles. I go to seek encounters with a group of films that present a rush of thoughts, which confront these times and this reality. I have no doubt that this year’s films from Asia and the world will express a new spirit, and I intend to join ranks in their creative struggle.

Born 1939. Adachi Masao became known for films such as Closed Vagina (1963) during his student days at Nihon University School of Art. He wrote progressive “pink films” for Wakamatsu Koji’s production house, and directed some. He collaborated on Red Army / PLFP: Declaration of World War (1971). Adachi left Japan to join the Palestinian liberation struggle in 1974. He was arrested in Lebanon in 1997 and sent back to Japan after three years in prison. In 2006, he directed Prisoner / Terrorist based on the story of Okamoto Kozo, member of the Japanese Red Army. His publications include Eiga e no senryaku (1974), Eiga / Kakumei (2003), and Le Bus de la révolution passera bientôt près de chez toi: Écrits sur le cinéma, la guérilla et l’avant-garde (2012). A retrospective of his films has been circulating Western cities in recent years.

AKA Serial Killer

(Ryakusho Renzoku shasatsuma) JAPAN / 1969 / Japanese / Color / 35mm / 86 min

JAPAN / 1969 / Japanese / Color / 35mm / 86 min

Staff: Adachi Masao, Iwabuchi Susumu, Nakamura Kozaburo, Nonomura Masayuki, Yamazaki Yutaka, Sasaki Mamoru, Matsuda Masao

Music Supervisor: Aikura Hisato

Music Performance: Togashi Masahiko, Takagi Mototeru

Editing: Yamada Sachiko, Ichimaru Fusako

Narration: Adachi Masao

Source: Adachi Masao Full Filmography Screening Committee

“Last Fall, in four cities, four murders were committed with the same gun. This spring a 19-year-old boy was arrested. They called him Serial Killer.” Following this opening text, the film shows us the many places where Nagayama Norio had once traveled and lived. The remote Abashiri, Hokkaido, where he was born, Itayanagi where he spent some years of his childhood, Hirosaki and Yamagata where he ran away from home, Moriguchi in Osaka where he apprenticed in a rice shop, the milk delivery where he worked while going to night school in Nakano, Tokyo, the Kobe port where he was caught as a stowaway, and others. Accompanied by a free-jazz saxophone and drums soundtrack and Adachi’s sober voiceover reciting the facts of the boy’s life, the film fixes its gaze on the landscape of the environment that was decisive in determining Nagayama’s course and consequence.